Heinrich Recognizes 100th Anniversary of Gila Wilderness

Heinrich provided keynote remarks at community celebration in Silver City over the weekend, passed resolution in the Senate recognizing historic anniversary of the world’s first designated and protected wilderness

SILVER CITY, N.M. – Today marks the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Forest Service designating the Gila Wilderness in southwestern New Mexico, making itthe first designated and protected wilderness area on Earth.

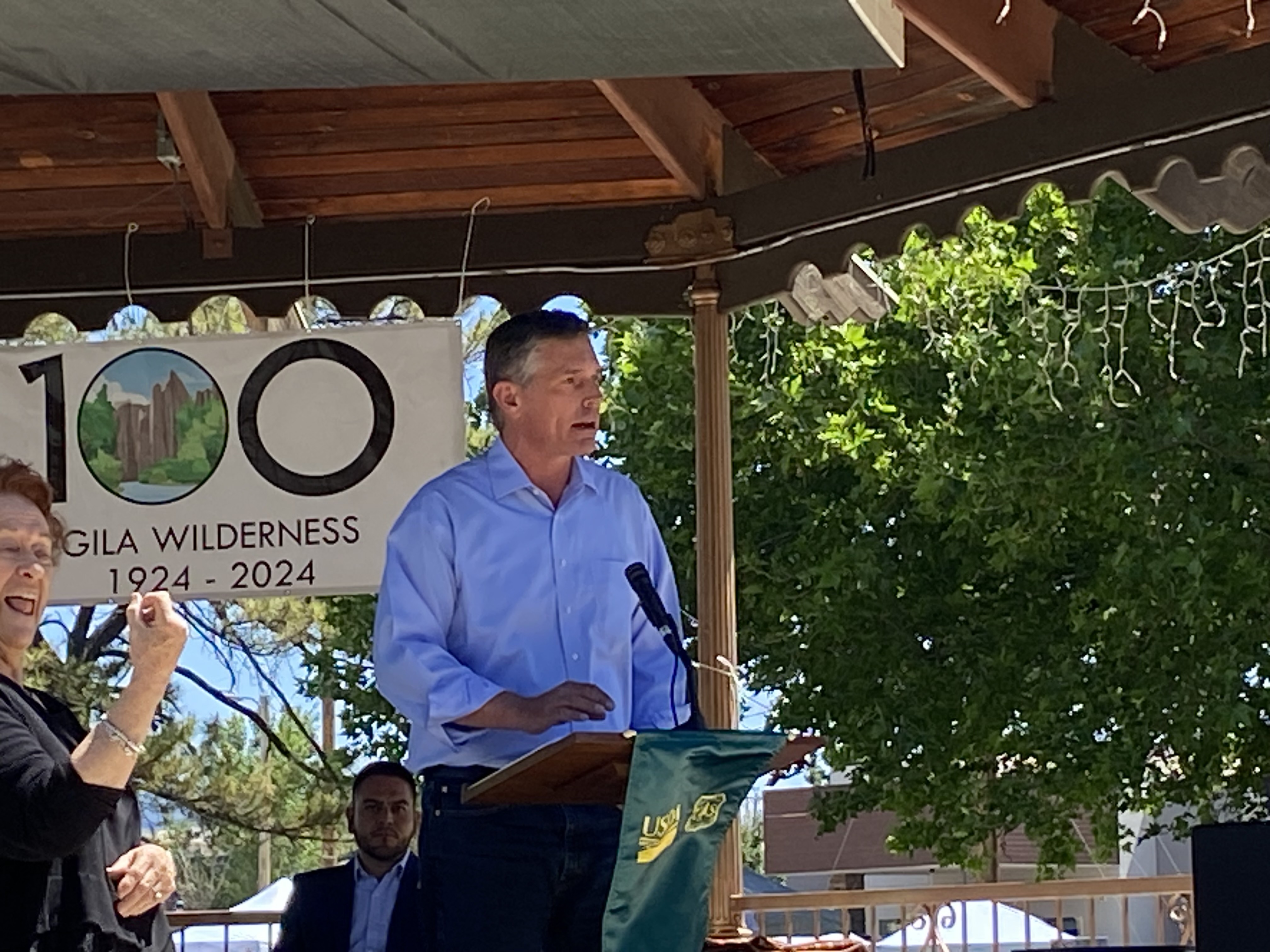

Over the weekend, U.S. Senator Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), a member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, delivered keynote remarks at a community celebration of the anniversary in Silver City, N.M., the gateway community to the Gila Wilderness.

“Knowing what the Gila Wilderness has meant to me and my family over these last few decades, I appreciate that wild places like this are still here. They’re here thanks to the visionary Americans and New Mexicans who fought to protect them,” said Heinrich.“I want this wilderness—and the free-flowing waters that support it—to be there for future generations to make new, lasting memories. I can think of no more fitting way to honor the legacy that has been built by so many over the first century of our world’s first designated wilderness.”

Last week, a resolution that Heinrich led to recognize the 100th anniversary of the Gila Wilderness passed in the Senate. Heinrich is also continuing to lead the effort to pass the M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which would provide enhanced protections for the watershed that supports the Gila Wilderness.

Heinrich’s keynote remarks as prepared for delivery are below:

Good morning, everyone.

I am honored to join you to celebrate the 100th anniversary of New Mexico’s Gila Wilderness—the first designated and protected wilderness area on Earth.

A little over a century ago, a young forester named Aldo Leopold first proposed setting aside wilderness areas to protect what he called the last big stretches of wild country.

For the ideal example, he pointed to the steep box canyons, rugged mountain ranges, and crystal-clear trout streams that cradle the headwaters of the Gila River.

Right here, in southwestern New Mexico.

From time immemorial, these have been the ancestral homelands to the Mimbres, the Mogollon, and the Apache peoples.

The headwaters of the Gila were actually the birthplace of the legendary warrior Geronimo.

By the time Leopold came to the region as an early Forest Ranger in the early 1900’s, the Gila Country remained largely roadless, untouched by extractive development, and mostly wild.

It was his vision for the Gila Wilderness that inspired the passage of the revolutionary Wilderness Act of 1964, which was stewarded through the Senate by New Mexico’s own Clinton P. Anderson.

That legislation set the foundation for protecting treasured wilderness areas all across our state.

From the Pecos and the Columbine-Hondo to the Ojito, the Bisti, the Sabinoso, and the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks.

Protecting all of these places started right here in the Gila.

My love of New Mexico did, too.

It started in my early twenties when I took an AmeriCorps position with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, working on Mexican gray wolf recovery.

That took me and a partner into the backcountry with camping gear for ten days at a time, surveying huge swaths of New Mexico and Arizona.

Our mission was to see if there were any remaining wolves in the wild and to document them if there were.

We’d stop every mile and howl into the darkness in each cardinal direction.

Despite all of our best calls, and a few truly awful ones, no wolves ever responded.

But what I did find was my first real exposure to gigantic, dynamic, and wild landscapes.

I had grown up exploring the outdoors in the woods and creeks around my family’s rural home.

My closest exposure to real wilderness came from caving and canoeing trips.

But this was the great outdoors on a scale that had been beyond my wildest imagination.

I still remember the first time I sat on the edge of Cooney Prairie watching herds of elk, mule deer, and pronghorn through my binoculars.

I was amazed — realizing we had places here in America teeming with wildlife, rivaling the wildebeest and impala on an African savannah.

And the Gila has taught me new lessons every time I’ve returned.

In fact, it was a trip into the backcountry well over two decades ago now that helped me chart a whole new course for the rest of my life.

I had been enjoying my work as an outfitter guide and educator.

But I wanted to find a new direction.

The terrorist attacks on September 11 had just sent a major shockwave through our country.

And I felt a deep calling to serve my community and country.

Around the same time that commercial flights were starting up again, I met up with a friend from college and drove southwest out of Albuquerque.

Over 53 miles, we backpacked and camped.

Sitting around the fire at our campsite along the Gila headwaters, we talked about our goals and plans for the future under dark skies lit up by the Milky Way.

I returned from that trip refreshed and determined to run for a seat on the Albuquerque City Council the following year.

For the last twenty years, I have found a sense of purpose in my public service that was borne out of that backpack in the Gila Wilderness.

I have continued returning as often as I can to the Gila, including with my wife, Julie, and our two sons.

Knowing what the Gila Wilderness has meant to me and my family over these last few decades, I appreciate that wild places like this are still here.

They’re here thanks to the visionary Americans and New Mexicans who fought to protect them.

But we are increasingly recognizing that to truly protect the Gila’s wilderness character for generations to come, we can’t stop with just the wild lands.

We also need to conserve the wild and scenic waters that sustain this precious corner of New Mexico.

When you look at our rivers today, particularly here in the American West, you’ll find that nearly all of them are now shadows of their former selves.

That's why we must keep up the fight to protect these Wild and Scenic Rivers.

Four years after passing the Wilderness Act in 1964, Congress passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968.

In the more than 50 years since then, designating some of our most treasured rivers as wild and scenic has supported enhanced water quality, economic development, and increased recreation opportunities.

This includes New Mexico’s Rio Chama, the East Fork of the Jemez, and sections of the Rio Grande and the Pecos.

Southwestern New Mexico’s Gila and San Francisco watershed absolutely deserve this same recognition.

I hope the next time we are together to celebrate the Gila, it will be to celebrate the passage of our M.H. Dutch Salmon Greater Gila Wild and Scenic River Act.

Can I get a round of applause if you’re ready to get this bill passed?

I completely agree.

When I think about why protecting both the wild lands and waters in the Gila is so important, I am humbled by all the New Mexicans who have devoted themselves to protecting this landscape over the years.

That includes my good friend, the late Dutch Salmon, whom we have named our Wild and Scenic Rivers bill after.?

A longtime nature writer here in Silver City, and even longer time avid fly fisherman, Dutch was such a consistent voice for the Gila River.

Dutch helped found the Gila Conservation Coalition, and over many decades of advocacy, he never stopped fighting to protect “his favorite fishing hole.”

If you are wondering how on Earth the Gila River is dam-free today, much of the answer lies in Dutch Salmon’s dogged activism.

As we look toward the next 100 years, we should focus on the Gila Wilderness that we will pass along to future generations of young New Mexicans.

In his Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold wrote, “I am glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in.

As both of my sons, Carter and Micah, have grown up exploring the wonders in New Mexico’s wild country, those words have taken on an even deeper meaning for me.

And it makes me remember three young citizen scientists fighting for the Gila River whom this community continues to mourn.

Last week, we marked ten years since this community experienced the tragic loss of three young champions for the Gila River.

Ella Jaz Kirk, Michael Mahl, and Ella Myers were classmates at Aldo Leopold Charter School and lifelong friends.

On May 23, 2014, they took off in a plane as part of the ecological monitoring research they were performing.

They were hoping to learn more about how recent fires and floods were impacting the upper watersheds in the Gila.

All three of them died when their plane crashed in a tragic accident.

Over the years, I have met with their mothers, who have continued their children’s call to protect the Gila River and the Gila Wilderness.

They came together to support each other, to cope with their grief, and to fight to uphold their children’s memory and love for the Gila.

They’ve spoken with me about how meaningful it would be to them if we can protect the free-flowing stretches of the Gila watershed as wild and scenic.

They want this wilderness—and the free-flowing waters that support it—to be there for future generations of young New Mexicans to make beautiful new memories.

Just like their children did.

I can think of no more fitting way to honor the legacy that has been built by so many over the first century of our world’s first designated wilderness.

###